Saving the Phelsuma antanosy and Telling Their Story

The rain hammered the forest all morning, dripping through the canopy and pooling along the sandy trails of Sainte Luce in southeastern Madagascar. Not the best conditions for spotting a sun-loving gecko. Even so, I welcomed the pause. It gave me time to reflect on why I was here again, eight years after my first visit to Sainte Luce.

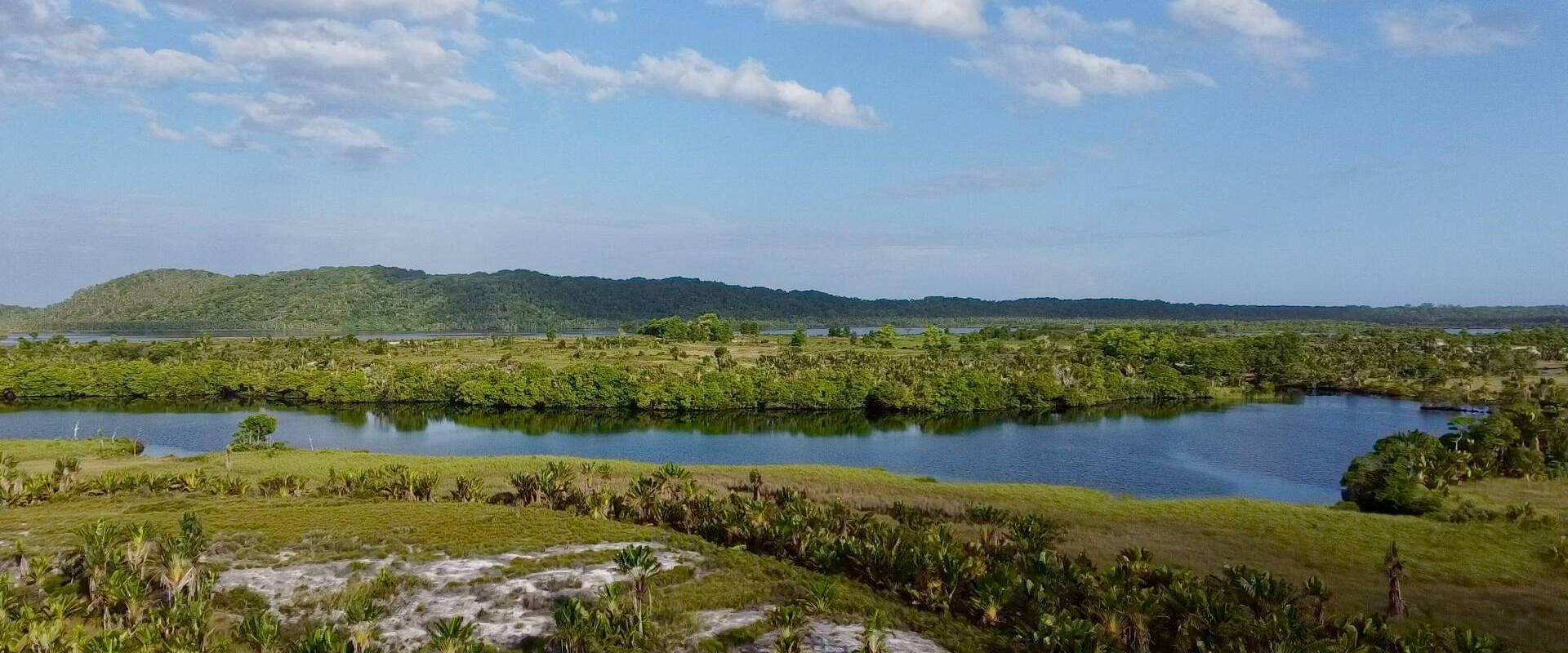

Back in 2017, I was struck by how unique these littoral forests are, thin ribbons of green clinging to Madagascar’s southeastern coast. Even then, their fragility was obvious. Today, they’re among the most threatened ecosystems on the island, home to plants and animals that exist nowhere else on Earth. One of those is the gecko I had traveled halfway around the world to see: Phelsuma antanosy.

Phelsuma antanosy is small, barely the length of my finger, but its story is immense. Formally described only in 1993, it lives in one of the narrowest ranges of any reptile on the planet: a few square kilometers of forest near Sainte Luce and similar small patches in Ambatotsirongorongo massif, 50 kilometers southwest of Sainte Luce. Its survival is tied almost entirely to one plant, a screw-pine known as Pandanus longistylus, which gives the gecko food, shelter, and a place to lay its eggs. Without Pandanus, there is no gecko.

That dependency has made P. antanosy an emblem of a bigger truth: saving species here isn’t just about biology, it’s about people. These forests fuel cooking fires, build homes, and provide income through agriculture and mining. The largest remaining population, in a fragment known as S7, overlaps almost entirely with a planned ilmenite mine.

This is where SEED Madagascar comes in. With decades of work in the region, SEED launched Project Phelsuma in 2024 with support from the National Geographic Society. The project’s idea is deceptively simple: move geckos from the high-risk unprotected areas into forests that are safe and legally protected. Of course, that means moving their Pandanus too. Teams transplant Pandanus screw-pines into protected fragments, and once they are established, carefully translocate geckos into them.

That’s the science. But what drew me back to Sainte Luce was the chance to help tell the story.

In the Field

After days of rain, the sun finally pushed through and we hiked out, an hour from camp through deep sand and tangled roots, to a patch of Pandanus. We stopped, scanning the spiny leaves. Nothing. Then a flicker of color: emerald green against the dull gray of a screw-pine trunk.

There it was. One of the rarest reptiles on Earth, perched in the dappled light, its crimson fork-mark glowing on its back. I leaned closer, careful not to startle it. After years of reading papers, planning equipment, and imagining this moment, I was once again face-to-face with Phelsuma antanosy.

It struck me then: this little gecko, in a fragment of forest most people will never see, carries a story about survival that’s global in scale.

For me, conservation is as much about storytelling as it is about science. I’ve always believed that a species like Phelsuma antanosy, tiny, overlooked, and yet utterly unique, deserves to have its story told loudly. To show the world why a small gecko in a small forest matters.

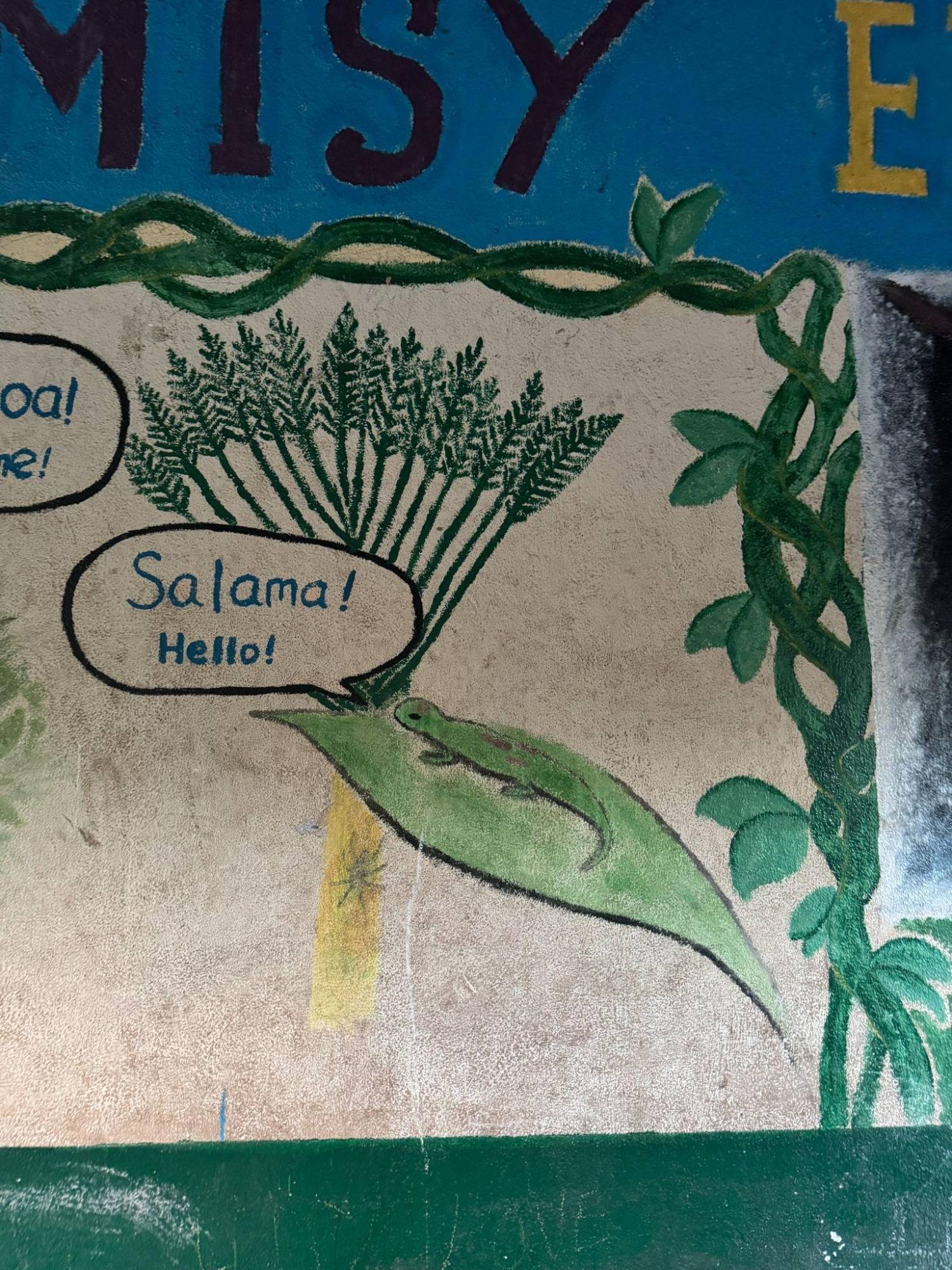

And in Sainte Luce, this story doesn’t belong to the gecko alone. Schoolchildren paint its likeness on their classroom walls. Local artisans stitch it into embroidery and wood carvings. Community leaders talk about it as part of what makes their home unique.

That’s why SEED’s work goes beyond geckos. Alongside Project Phelsuma, they run programs in education, community health, water and sanitation, and sustainable livelihoods. Supporting families here is not separate from conservation, it is the only way conservation works.

Headed Home

The project is still in its early stages. A trial translocation moved a small number of geckos into newly planted Pandanus groves. Post-translocation monitoring efforts are underway, but the long-term outcome remains uncertain. Wildfires in early 2025 underscored just how precarious this work is, destroying swaths of habitat and further compressing an already fragile population.

When I left Sainte Luce in 2017, I carried with me the weight of how fragile it all felt. This time, I left with something else as well: hope. Hope rooted in both science and community. Hope that if people and conservation move forward together, the green flash of Phelsuma antanosy will still endure in the shifting light of the forest. How long it lasts will depend not just on science, but on whether the people who share its home are supported in protecting it.

This work is part of Project Phelsuma, led by SEED Madagascar in conjunction with Young Explorer Avery Tilley with support from the National Geographic Society.